THE LAW AND THE PROPHETS

directed by Joshua Vis and Eric Schrotenboer

120 min. Amorzao Productions 2023

“Entertaining” is hardly a word one might choose to describe a film exposing the astonishingly layered, brutal matrix of laws, policies, and practices that Israel employs to control Palestinians. Still, The Law and the Prophets—two hours long—is a compellingly filmed, fast-paced, thorough look at the daily threats and challenges that Palestinians face.

The film opens with pastoral scenes of Lifta, one of the hundreds of Palestinian villages that were ethnically cleansed by Jewish militias following the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. In a voiceover, Israeli guide Yahav Zohar tells how, as a child, he played in the village’s remains situated on a slope just outside of Jerusalem. Lifta, he recounts, had “unofficially become a park to the [surrounding Jewish] neighborhoods in which to play and to picnic.” Once he grew up and learned the village history, he says, “It changed the meaning of Lifta for me from a playground to a place that reminds me also of the Nakba [Arab for catastrophe].“

Then, as if introducing the entire film and not just commenting on the account of Lifta, Independent journalist Jonathan Cook says, “The story here is an uncomfortable one for Western audiences to hear….”

Cook points to the difference between colonialism and settler-colonialism. “Colonial societies, Britain being a good example of one, went there to exploit the native population,” he says. “Settler-colonial societies go there to replace the native population…. It comes at a terrible price for the local population. It can lead to genocide, ethnic cleansing, to apartheid.”

The film was the idea of Joshua Vis, an ordained minister with a PhD in history. He hosts immersion tours to Israel/Palestine. When asked by Mondoweiss why he and co-producer Eric Schrotenboer made the film, Vis said, “I’d been working in the area, bringing people for years to meet with these incredible people. What they had to share is so important, we asked, ‘How can we amplify their voices.’”

Using first-person accounts, Vis’ narration exposes the viewer to what he describes as a “veil of legitimacy” concealing Israel’s oppression of the Palestinian people. He says,

I thought that the Israel/Palestine conflict was complicated. But it’s not complicated… One people group sees itself as superior to another people group. And this superiority breeds contempt which leads to systems of oppression. In the 21st century, those systems must be given a veil of legitimacy, especially when the group deemed superior claims to be democratic and morally upright. Thus, the mechanisms of oppression are hidden behind the veil of security, of law and order. And because Western audiences are prone to sympathize with the Jewish people, this veil is sufficient.

“But once you see behind the veil,” Vis continues, “you cannot unsee what lies there. You cannot unsee the ugliness of oppression on the Palestinian people.”

The context of current events is briefly described: the UN partition and the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians in 1948-49. But the film is focused on the continuing Nakba.

Co-founders of Military Court Watch Gerard Horton, an Australian attorney, and Salwa Duaibis, a Palestinian citizen of Israel, describe how children 12-17 years old are taken from their homes in the middle of the night and threatened with prosecution in military courts in contravention of international laws and human rights conventions. The viewer sees footage of children suffering interrogation by Israeli security forces who use threats of intimidation—“you’ll go to prison for a long time,” “we’ll arrest your mother, your sister”—to gain confessions and/or press for collaboration.

Filmed in his Ramallah home, Palestinian-American Sam Bahour describes the challenges faced in his building a Palestinian telecommunications system. He explains how the Oslo Accords were written to cement Israel’s control of the Palestinian economy. “Who’s in charge of the pace of our development?” Bahour asks. “Ultimately, Israel calls the shots.” The Oslo accords, Vis explains, “did not end the occupation; they systemized it.”

On the farm that his family has worked since before his grandfather obtained ownership papers from the Ottoman Empire, Daoud Nassar tells how the Israeli military and the Israeli court system have aided settlers in their efforts to take the land.

Journalist Cook describes a “policy of Judaization throughout Israel and Palestine.” As an example, he points to Jewish development around Nazareth, a Palestinian city in Israel. Though Palestinian citizens pay taxes, the city is denied resources and access to land, limiting their growth and development. Footage shows the effects of Israel’s occupation of tourism as hundreds are seen visiting one of Christianity’s holy sites in Nazareth, the Basilica of the Annunciation, then departing on buses, depriving Arab shopkeepers, restaurants and hotels from sustaining business.

Itamar Shapira, a former Israeli soldier and co-founder of Combatants for Peace, explains Israel’s use of the holocaust and a history of victimhood to teach a narrative of fear and isolation on the part of Israeli Jews—excusing them from getting to know Palestinians and justifying the occupation.

In one of the film’s more revealing scenes, tour guide Yahav tells how Palestinians are enticed to collaborate with their occupiers through an Israeli intelligence officer assigned to each West Bank village. “Not for money,” Yahav says. “Not for the love of the Israel government.” But suffering from a strangled economy, to feed their families, to obtain a permit to work in Israel where the wages are much higher. The permits can be revoked at any time, Yahav says.

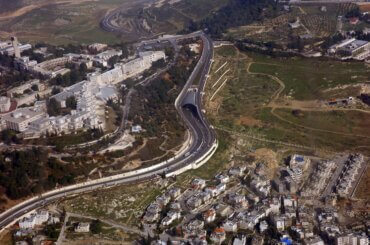

The film’s well-woven tapestry showcases nearly every other aspect of Israel’s matrix of control, including the effects of the apartheid wall and illegal settlements, the two-court system in the West Bank, home demolitions, Israeli suppression of Palestinian resistance, and the elaborate permit system that controls nearly every facet of Palestinian life (access to employment, education and medical services; who Palestinians can marry, where they can travel).

The Law and the Prophets—the title is a phrase often used to describe the whole of the Hebrew scriptures—succeeds in informing those who know very little about the situation and, at the same time, adds to the knowledge of those who have been following the devolving situation for years.

Vis and Yahav admit that their work and witness are limited. Yahav could be speaking for both when he says that he continues to guide groups “with the hope that it somehow leads to a wider understanding, that it leads to change, although I cannot say I see clearly how….”

Vis ends the film with a sobering tribute to those who shared their stories, those whom he describes as prophets, and truth-tellers in our day. He says they join…

…countless names lost to history: dissidents, activists, journalists, lawyers, farmers, slave, musicians, sisters, brothers, mothers, fathers, daughters, sons, friends—each one willing to risk something, to lose something, lose respect, lose money, lose relationships. A life of choosing to lose.

The life of most prophets is a life shaped by defeat. This is the secret of the prophets. They find meaning, joy even, in a worthy struggle, a struggle rooted in honesty, decency, integrity, courage and service. Victories are satisfying, but they are fleeting. The worthy struggle is timeless.

A major media outlet has not yet picked up the independent film. Earlier this month, it was the choice of Voices from the Holy Land (VFHL) for its monthly Salon. 950 persons viewed the film free of charge at a time of their own choosing. Nearly 400 persons watched the panel discussion moderated by Mercy Aiken of the Network of Evangelicals for the Middle East, and featuring Vis, Muhanad Al Qaisy of the Joint Advocacy Initiative, and Chase Carter, Communications Director for the Center for Jewish Nonviolence.

Sunday, April 16, VFHL will host a panel discussion on Episode 4 of Al Jazeera’s The Lobby-USA. The documentary follows an undercover journalist posing as a pro-Israel volunteer who gets unprecedented access to the operations of Israel lobby groups in Washington, D.C. Register to join the discussion and receive access to the film.

Our colleagues at Hasbara U tell us that the Palestinians don’t want peace, so what can Israel do but continue its current policies?

Well, 972 ran this letter – “The following is a letter by Tareq Barghouth, a Palestinian political prisoner who in July 2019 was sentenced to 13.5 years in prison, after being convicted of committing shooting attacks against Israeli soldiers in the occupied West Bank.”

https://www.972mag.com/tareq-barghout-prison-letter/

Well worth a read, but there’s one paragraph that caught my eye – this is right before the Second Intifada:

“Three years later, I was arrested and sentenced to a year in prison after I was convicted of setting fire to a rental car belonging to an Israeli company.When I was released from prison, reality was completely different. Dramatic changes had turned the political situation upside down. The Oslo Accords and the peace process had taken off. Palestinians gave olive branches to Israeli soldiers instead of throwing stones and Molotov cocktails. Palestinian flags were waved without any disturbances. I said to myself that the dream had come true, that finally we would be free and equal like every other nation.”

Netanyahu has admitted to sinking Oslo.

If the film makers want the world to see this important film, perhaps they should make it available. Post it on YouTube. Absent that, it is more than likely the film will be viewed only by a relative handful of the already convinced, and in a couple of months will be forgotten.